|

|

|

|||

| About me |

||||

| Guest book

|

Historical essay For those who have forgotten but do not want to forget... |

|||

ESSAY: |

By A. VOLOGODSKY and K. ZAVOISKY | |||

Мертвая дорога часть 1

Dead Road part 1 (English) Dead Road part 2 (English) Dead Road part 3 (English)

Непонятно только, зачем это нужно человеку?

|

DEAD ROAD - MUSEUM OF COMUNISM UNDER THE OPEN

PART 2

2. Catching at ShadowsThe center of the construction was temporarily located in the fish-factory district of Salekhard. The newcomer civilian workers lodged in private flats. The construction management occupied a school building. Not far away a plot of land was enclosed with barbed wire, marking the place for the “headquarters column” of prisoners working under the railway building Administration. The Salekhard wood-working plant switched over to serving the construction needs, turning into a slave enterprise complete with watch and guard. Rows of barbed wire were drawn up farther along the bank of the Poluy river, where the laying of rails to the Salekhard station was started, and where a special GULZHDS settlement was being hastily built. The slaves were brought to the columns by lorries under escort, and in absence of transport they were driven on foot surrounded by guardsmen. The Labytnangy settlement on the left bank of the Ob became the transit center via which the main slave manpower was being brought to the Dead Road. Building materials as well as equipment and machines necessary for life and construction were brought via Labytnangy which GULAG, as was mentioned above, had already connected by a branch line, with the Pechora Railroad. The quiet, patriarchal Siberian town of Salekhard was stunned by the sudden influx of builders, the lustre of golden shoulder-straps of high GULAG chiefs, the roar of unknown building machines, and the cheerless view of gray prisoners’ columns. From here the builders moved East in the direction of Nadym. They had to begin preparatory work immediately after the issue of the Council of Ministers’ decree, in the middle of the Polar winter, without prospecting, with no design, nor estimate documentation. A winter road was laid out in the snow with the help of a tractor train, along which were hastily deployed production columns of prisoners—involuntary heroes of the new “Great Construction of Communism”. The prisoners themselves built, at sub-machine gun point, camps they were to live in. By summer the building of quarries, embankments, pipes, bridges had already begun on the first sections of the railroad. In order to speed up the work former Building Administration 501 (SULZDS) which had just given up the construction of the half-built road to Stone Cape, was divided into two construction giants: Ob Administration 501 with its center in Salekhard, that was to lay the western part of the line 700 kilometers long, and Yenisei Administration 503 with its center first in Igarka and then in Yermakovo, which was to lay the 600 kilometer-long railway from the East to the West, to meet Administration 501. Communication between the builders and the administrations was maintained first by radio and later on by the pole telephone-telegraph line which had been drawn by the prisoners from Salekhard to Igarka along the future railroad. For inspection of the construction the authorities used the services of field and military aviation. Both construction Administrations were part of the GULZHDS system, which in its turn was under the USSR MIA jurisdiction. According to the GULAG leadership plans the builders of both Administrations were to have met by 1952-53, on the bank of the river Pur, approximately in the middle of the 1, 300 km-long line. They understood on the top that efficiently to erect a huge construction on permafrost in a short time was an unrealizable task. For this reason the Administration was in a hurry first to lay the rails along the line without gaps, then to provide for the functioning of the railway at minimum capacity and thereafter, when trains would run, to complete the construction in real terms. In point of fact, even in its final state the Salekhard-Igarka Railway was to present a pitiable sight: the single-track with double-track sections, each 9 -- 14 kilometers long, was planned to launch at most 6 trains per twenty four hours.

The organization of the two Administrations’ work proceeding from the opposite direction was in addition characterized by almost complete absence of access roads in the region of the future railway. The builders moved forward in the following way: first, in winter time, they conveyed to the sections everything necessary for the construction during the coming season: slaves, building materials, equipment, foodstuffs. Then, along the already built highway, fresh forces were conveyed to be advanced further on for future use in the following building season. The leadership refused right away to build permanent highways along the railroad. In summer, wherever possible, rivers were used as access roads. As has already been said, the Communist government didn’t allow the contractors any time for prospecting work. Construction began simultaneously with the survey. Unforeseen circumstances caused at times the designers to lag behind the builders. Thus, for instance, on coming into the field, the designers of the USSR MIA Railway-Project, who had on more than one occasion devised GULAG railway construction schemes, discovered that the maps of the future Railway region were not detailed enough. So, the surveyors had first to draft new maps by means of air photography. It brought about an absurd situation: the delayed designers were often compelled to draw the railway line proceeding not from the local conditions, but from the location of the GULAG camps which had already been built by that time. The survey of the Dead Road as a whole, was finished only in 1952, just by the time this “Construction of Communism” had ceased to arouse enthusiasm among the high authorities, and was dying down.

The main part of the construction work on the road consisted in erecting the embankment for the future railway. In the exceptionally complex geological conditions of the region this kind of work proved to be too laborious, though the embankment was being built only in summer time, by simplified technology, and was formally approved by understated technical standards. Luckily enough, there was sand in abundance in the river valleys, wherein a considerable part of the line was laid. The sand was delivered to the embankment from the near sand-pits by dump trucks which were often stranded in the mud. Almost all timber was to be brought from other places and floated down the Ob, Taz and Yenisei rivers, in whose upper reaches it was stockpiled by the GULESLAG prisoners. Later on the railway itself began to help: small shunting locomotives with several goods trucks delivered the necessary building materials along the laid sections of the road.

It should be noted that at first the government lavishly supplied the construction. An unprecedented (by GULAG standards) amount of new heavy equipment was delivered from the center to the far-off spaces of Siberia. Even excavators were no rarity there. But the main instruments of earth-moving work remained the prisoners’ pick, shovel and wheelbarrow. The embankment was mostly raised in the old way: in single file, straining every nerve, the prisoners would push their heavily loaded wheelbarrows up a steep wooden ladder. On emptying the wheelbarrow each prisoner received a tag from the accounting clerk, and putting it into his pocket, would go down by another ladder. Other prisoners on the top of the embankment, levelled the sand with wooden rammers, while the guardsmen were dozing around the fires. The delivery and laying of rails was carried out by special laying stations—trains of several trailers running along the built part of the railway. The workers-prisoners were kept in heated goods vans under guard. All the work of laying rails was done by hand. Wearing tarpaulin gauntlets the prisoners dragged the rails with long iron tongs up the embankment to put them upon the fixed sleepers. This work, like almost all the other kinds of work at the Dead Road construction, was laborious and inefficient. In places where the railway was to cross streams that were shallow in summer, the builders erected wooden bridges across them or enclosed them in large-diameter concrete tubes placed under the rails. Hundreds of such crossings had to be built. The railway also crossed dozens of rivers including such high-water level rivers as the Taz, the Pur, the Nadym. The erection of bridges across such big rivers was a hard, and technically complex task requiring substantial additional materials and labour expenditures. For this reason at such crossings the builders at first usually erected temporary bridges on a detour, which later on, after the completion of the railway, were to be gradually replaced by permanent bridges. Envisaged were train-ferries across the river-giants the Ob and the Yenisei in summer, and a seasonal railway on the ice in winter (such an ice rail-crossing across the Ob was actually built and was functioning during the construction of the railway!). In addition to the main work, the construction required the provision of numerous auxiliary economic and railway services. Along the road were being built engine depots, repair shops, plants, woodworking centers, iver moorages, dwelling houses and office buildings, and numerous other economic units. The building work overturned the life of the entire region, subordinating vast territories to the requirements of the railway project. The above mentioned settlement of Yermakovo where the Eastern Part Administration was situated, grew into a city with a population of 20 thousand, not counting the prisoners in the surrounding camps. The first signs that the country’s supreme leadership began to lose interest in the railway appeared in 1951. The idea of a gigantic port being built in the Northern seas for some reason or other, forfeited for Stalin its former attractiveness. The Politbureau was gradually subscribing to the opinion that the government and its GULAG had again been too rash in taking the decision to build the Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line. Despite the fact that many talented engineers working at the construction adopted simple but most effective original designss of railway laying in conditions of permafrost, in most cases their ingenuity was to no purpose, for the built railway line was grossly imperfect. The embankment raised in a hurry and by simplified technology was floating, washed out by spring waters, and blown off by winds, to sink into the swamps almost all along the railway. The bridges built on permafrost swelled and warped. As a result the newly built railway already required for its operation intensive efforts of numerous GULAG camps situated along the line. On the functioning parts of the railway the trains moved at a speed of 15 km/hour, often being derailed. In one of the deserted camps the authors’ expedition found, in 1989, a poster eloquently illustrating the situation: “Railwaymen! Put the tracks in good shape. Don’t let the trains get derailed! “Which other railway in the world has ever seen such a slogan! Nevertheless the GULAG was determined to continue the building of the Railway Line until its final victory. In May 1952, a special commission was formed to consider the technical project worked out by the combined ZHELDORPROEKT Northern Expedition, and in October of the same year the project was sent to the State Building Committee, USSR CM, for official approval. This document proposed that the government allot another 3 billion roubles in addition to the three billion already spent, to put the Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line into working condition. On March 25, 1953, soon after Stalin’s death, government deree No. 895-383ss, put a stop to the ruinous construction of the Chum-Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line. By that time Administration 501 had laid 400 km of railway, and Administration 503 -- 160 km from the city of Yermakovo in the direction of Salekhard, and some railway sections on the right bank of the Yenisei in the direction of Igarka. On two railway sections—Salekhard-Nadym (350 km) and Yermakovo-Yanov Stan (140 km) -- regular working traffic of trains was conducted. Besides, this Administration had built in Yermakovo a timber wharf, a saw-mill, a wood-working plant, a motor-repair works, an electric power station. A construction branch was established on the river Taz, which built a large settlement there, erected in most arduous conditions, an embankment, and laid a 10-15 km-long railway in the direction of Yermakovo. By the time the construction work was discontinued the two Administrations had expended over four billion rubles. From the moment the decision was taken to stop the construction, the railway began to die rapidly, turning into that which is now called “the Dead Road”. After an amnesty was declared for certain categories of convicts, the prisoner columns began to thin out. The propaganda enthusiasm waning, the towns and settlements became ever more deserted. With Stalinism weakened, the employed civilians moved to more lived-in regions. Everything that had for four years, been giving life to that vast region of Siberia, was overnight rendered necessary to nobody. But the authorities still had many economic obligations in the region: it was necessary to do something about the immense number of buildings, transport units, implements and other equipment located on the vast spaces of the construction. At first they tried to conserve the construction and all its property, but later they came to regard such approach to the matter as too troublesome and unprofitable. Part of the most valuable equipment was taken back to the lived-in regions. In the 1960s, the Norilsk plant removed the rails from the right bank of the Yenisei. It was seemingly decided to destroy the articles of daily use, to prevent the USSR citizens from getting them free of charge. In one of the railway camps the authors’ expeditions found an enormous cemetery of articles: heaps of boots cut to pieces with knives, piles of aluminium bowls, each with a hole acurately pierced with a bayonet just in the middle. It must have been an impressive sight to watch the USSR MIA guard soldiers destroying, by secret orders of the GULAG chiefs, the camp plates and dishes with their service weapons! It is also likely that what we took for bayonet traces might be the traces of common prisoner’s picks: the prisoners themselves might have been made to destroy the camp property. Whatever the case may be the destruction work required strenuous efforts. That’s why the bulk of the camp property was left to the mercy of fate. In 1957, four and a half years after the construction was stopped, a Lengiprotrans (a designers institution in Leningrad) expedition examined the western part of the railway from Salekhard to Nadym in order to determine its state. The expedition arrived at the conclusion that approximately one third of this part of the railway was utterly unfit for operation, the embankment required serious repairs, dozens of bridges wanted rebuilding as their bulging had reched an enormous immensity of about half a meter. Of all the erected constructions the only one still functioning was the pole-telephone-telegraph Salekhard-Igarka-Norilsk Line which had by that time been transferred from MIA control to the control of the USSR Ministry of Communications. The workers of the railway control points stationed at 30 km intervals, still maintained, using their own resources, the preserved parts of the railway in partly working condition, so that trolleys with light-weight trucks could run along the line, delivering, in summer, food and equipment to the railway. In the early 1960s, enormously rich deposits of oil and gas were discovered in the vast area between the Ob and Yenisei rivers, which started the commertial development of the region. The uncompleted Dead Road which crossed this region, was, in December 1963, brought to the attention of the country’s new leadership, in the memorandum by P. K. Tatarintsev, author of the Chum-Salekhard-Igarka Railway Line, already mentioned above. His arguments in favour of the construction being resumed were much the same as in 1953. The new government bearing in mind Stalin’s failure, considered the project too risky and rejected the designer’s suggestion—new times had set in, and the GULAG was no longer the organization it had been before. The leadership designated a way out of the situation in the construction of gas pipe-lines from the deposit regions to the European part of the USSR. A single-track-railway was laid to Urengoy, to provide easier access to the region from the Surgut-Nizhnevartovsk Line. However, the problem of resuming work at the Dead Road had been debated in the USSR designers organizations until the mid-1970s. At the end of the 1980s, expeditions of the authors of the present album examined the Eastern part of the Railway that had been completed by 1953. The photographs included in the album speak for themselves. In the most profound sense of the word, these terrible industrial landscapes of the still-born construction symbolize the natural finale of all the undertakings conceived by the Bolshevik system which had been staking on falsehood, violence and forced labour.

3. Dead Road SlavesAs has been mentioned above, work in all the sections of the Salekhard-Igarka Railway began with the setting up of so called “production columns”—complexes of buildings, each consisting of a prisoners camp, economic premises, barracks for the guards, and dwellings for the authorities. Those columns were placed at each 5 -- 7 km along the whole length of the railway section to be built during the coming year. At intervals of 60 km, railway stations were built with side-tracks, ten to twelve columns on a stage of the line forming a unit. Men’s and women’s columns were placed separately, but men—and women-prisoners did the same work pouring gravel and sand, digging the frozen ground, loading and unloading transport waggons. Only those women were lucky who worked at the Central Sewing Plant where they were doing just women’s jobs—sewing quilted suits for the prisoners. The sections included not only building columns whose people were led out each morning with picks and shovels, crows and wheelbarrows to raise and level the embankment. There were columns to serve different purposes. For instance, transport columns were made up of railwaymen: engine-drivers and stokers, railway engineers and repairmen who serviced the railway. The road requiring continuous capital repairs, the camps kept on functioning even after parts of the line were put into operation. The principal burden of subduing nature fell to the parties of prisoners-pioneers. From habitable places they were sent forward, to areas where the rails ended. They were brought by sledges hooked to tractors, or by formations on foot, and from afar at times—by waterways, to remote places the designers appointed. There the prisoners were literally left to the mercy of fate, if not to count the constant GULAG guardianship. Those landing parties had, in the shortest possible time, in the most deplorable conditions, to render the place habitable and prepare a base for life and work for the arriving slave reinforcements. An eye-witness, engineer-surveyor A. Pobozhy draws in his notes an impressive picture of prisoners-pioneers unloading, in summer, enormous lighters and barges which had brought, by the Northern Sea Route to the bank of the Taz river, new slaves together with engines, railway cars, rails and sleepers. This GULAG landing party probably started the above-mentioned construction section of Building Administration 503 which laid the railway line from the Taz river in the direction of Yermakovo. Prisoners’ landing parties were not always brought to their destination in summer time. In the cold months their situation was more horrifying. They often couldn’t get wood to build shelters—there was only the tundra around. Until timber was delivered they had to live in most primitive conditions—in mud-huts or tents kept warm with “bricks” cut out of peat and moss turf. Polar cold and dampness penetrated into those dwellings nomatter how well the chinks were stuffed up with moss. Plank-beds were made of poles cut in the near tundra brushwood scientifically called “oppressed wood”. The prisoners slept on the plank-beds without mattresses, as was the rule in the GULAG. Their own wadded jackets and pea-jackets served them both as bedding and blankets. As the development of the area went on, building materials were delivered, and, the primitive temporary dwellings were replaced by capital wooden buildings more suitable for durable living, and in large centers—even by frame-barracks with plank-beds. In all the columns of the Dead Road the capital camps were built by one and the same scheme elaborated to the smallest detail, by the GULAG Administration as far back as the 1930s. Each camp was a square plot of land 200x200 meters, fenced off by 3 rows of barbed wire, which the GULAG authorities never ran out of. A high wire barrier with a peak was erected between two lower ones. In the corners of the square there were guard watch towers supplied with searchlights which at night poured blinding light into the zone, to prevent the prisoners who might conceive plans of escape, from hiding. For this important regime purpose in addition to building materials, barbed wire and instruments, movable power-stations were first thing delivered to each camp. On the territory of the camp there were put up 5 or 6 prisoners barracks which were divided into two halves with separate entrances, each to house 40 people. In the middle of each half there was a stove made of bricks or of an old metal barrel. Along the walls were placed two storey plank-beds. On the territory of each camp there was a canteen, a bath-house for prisoners, sometimes a provision stall, a storehouse for personal belongings, a first-aid post, a library, a special section which dealt with the registration of prisoners and distribution of the work force, an operative-chekist department (OCHD), a so-called cultural and educational Department (CED) and others. Several houses, very much like camp barracks, were built near the camp, for the guards and dwellings for the authorities. It’s interesting to note that they sometimes allowed certain artistic liberty in the camp architecture of the Dead Road, subordinated as a whole to the purpose of crushing man’s individuality and keeping his psychological state at the level of beasts, which was typical of the Stalinist GULAG. In the half-ruined camp buildings, among the oppressively gloomy monotony, even now one can come across some decorative excesses pleasant to the eye: arches with ornamental decorations, summer-houses built by the prisoners themselves, and even still life pictures painted on the plastered barrack walls. In each camp there was an indispensable penal solitary confinement isolator (PSCI) -- an inner camp prison, which was used for the suppression of those to whom camp life didn’t seem severe enough. PSCI situated near the watch-tower in one of the camp corners, was enclosed with an additional fence of barbed wire. It consisted of two unheated solitary cells, one common cell for 4 -- 6 people, and a warm room for the guard. The tiny cell windows had thick iron bars on them. The wooden doors with spy holes for watching the arrested were sheeted with iron. The prisoners were fed on cold food rationed according to the lowest standards. Life of the railway camps in no way differed from that of the rest of the GULAG. L. Shereshevskiy, a former prisoner of the Dead Road, describes camp life in the following words: “Getting up early, bread ration, fish skilly, kasha (gruel) of God knows what grain—either boiled pearl-barley or millet blue because of the cauldrons’ poor tinning, boiled water without anything; roll-call of prisoners, taking them to the railway to work at a place fenced off by poles, with inscriptions on tablets “Restricted Area”, short smoke breaks by the fire, return to the zone in the evening under escort, and hard plank-beds. For entertainment there was the radio, sometimes newspapers, checkers and dominoes. The criminals drank very strong tea (so-called “chefir”) and played cards. After the evening roll-call, restless sleep in the cold barrack”. When the construction was in full swing, the prisoners working at the Railway totalled 70 – 100 thousand people. Usually one camp contained 400 – 500 people. Larger camps were built in places where work was most intensive: at the construction of big bridges, plants, settlements, etc. The functional organization of those camps was approximately the same. Although up till now the GULAG archives have remained secret, we know something of the people brought against their will to that gigantic Northern construction. Having no access to the archives, we are telling our story mainly on the basis of the oral evidence of a few survivors, former builders of the railway. Taking into account the scant information sources, the authors’ expedition to the Dead Road was lucky to find, in 1988, the card-index and summary account of prisoners’ movement of one of the camps in the Eastern part of the line. © A. VOLOGODSKY and K. ZAVOISKY, 1991 |

|||

| |

||||

|

|

|||

| "Пес возвращается на свою

блевотину и вымытая свинья идет валяться в

грязи". 2-е Посл. ап. Петра, 2:26 |

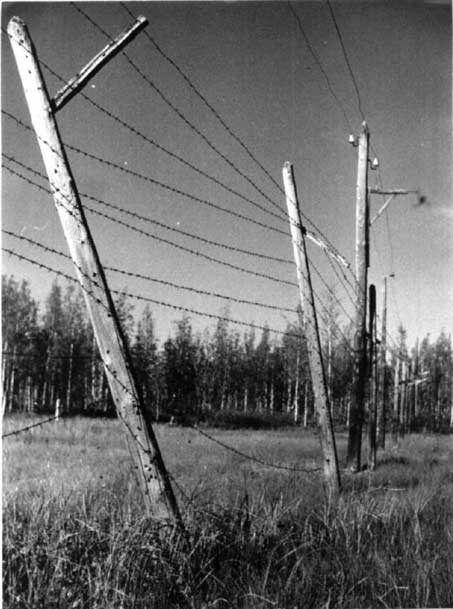

По сибирской дороге столбы. Photo by A. Vologodsky | |||

|

|

||||